Motown.

Motown.

With the exception of a New York neon post late last month, my blog has been offline since mid-November. That’s when I did my final post from the return drive from California to New York on the historic Lincoln Highway. It’s therefore past time to get cracking again and return in this blog, dear readers, to the roads less traveled.

These next few posts will be from my photo archive and cover an amazingly fun and interesting side trip to Detroit in September 2016.

The Motor City. The D. Motown. It’s an extraordinary place. Where do I start? How about briefly with some history connecting Detroit to the Lincoln Highway narrative in so many of my previous posts?

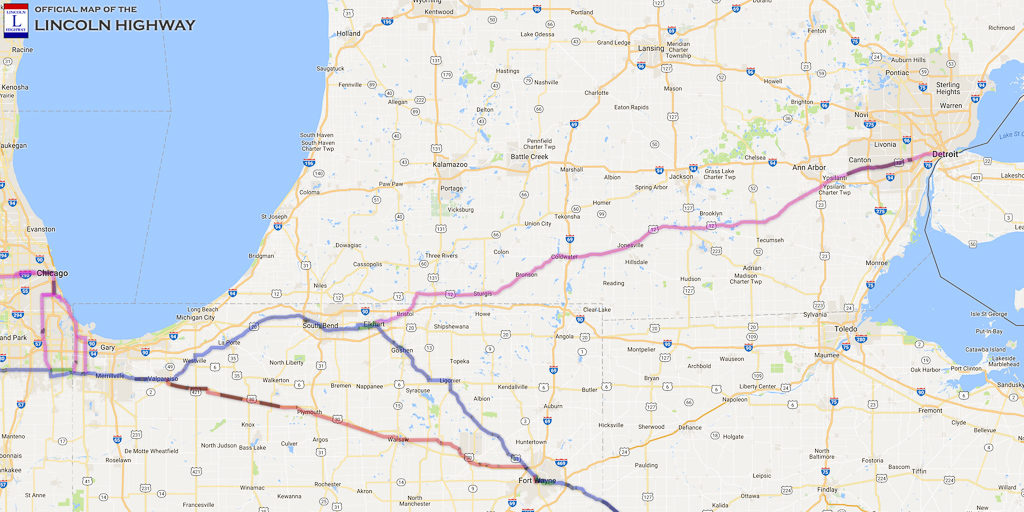

The Lincoln Highway – the country’s first transcontinental road – was first organized on July 1, 1913, at Detroit, Michigan, and its headquarters established there. That made sense. After all, the Lincoln was about automobile travel, and what better place to set it up than in ascending Detroit, which at that time was well on its way to becoming the Motor City and the world center of car production? (The Ford Model T had entered production in 1908, and that was the game changer for Detroit and the industry. More on Ford and the Model T below.) The Lincoln Highway Association archive was donated to the University of Michigan’s Transportation Library in 1937.

Strictly speaking, the transcontinental Lincoln Highway as such did not run through Michigan. Set out below is a portion of the Lincoln Highway map showing what is called an “auxiliary” route and which runs from Elkhart, Indiana, to Detroit. I took the interstate when I drove to Detroit and didn’t drive the feeder route on the map.

The September 2016 visit was my first time in the Motor City. My impressions ran the gamut. Fascinating, stimulating, frightening, saddening, surprising, encouraging…it’s all of that and more.

It’s a bewildering place. One minute it would knock me off my feet – incredible architecture (a Mies van der Rohe, the iconic Albert Kahn buildings, the other art deco beauties), gorgeous Belle Isle park, the Detroit Institute of the Arts and other museums, the surviving mansions, the historic downtown, the revitalized residential neighborhoods with their stunning homes, the street art, and much more. At its height this city must have really been something. Then I would drive through an industrial wasteland with huge abandoned factories, and burned out and otherwise abandoned buildings, or a truly impoverished and challenged residential district, and wonder how this could be the same city and for that matter the same country. How did it come to that?

The time there flew by. One thing is certain: I’ll be back. More thoughts to come in some future posts.

In the meantime, this first set is about industrial heritage and specifically the auto industry there. If anything captures the rise and fall of Detroit, it has to be car production there. That industry was a key part of its rise and its incredible wealth, and it also played a decisive role in the city’s long, sad decline. What better place to start than with cars? I think the carheads out there may enjoy this post.

I am going to use some buildings to tell the story. Some of these are tremendously significant to US industrial heritage. Some are from the height of Detroit’s wealth and importance, and it shows. Some are icons of industrial decline. Agony and ecstasy.

You’ll see a lot of Ford Motor Company sites in this post. It isn’t intentional; it just happened that many of the historic automobile sites in the city relate to Ford. Rightly so given Ford’s place in US industrial history.

(We were a Ford family. When I was growing up in the 50s and 60s in postwar America (before the VWs, Datsuns and Toyotas started to win big market share), a lot of families were very particular about the cars they bought. There was tremendous brand loyalty. Ford families didn’t buy GM or Chrysler cars…but that is neither here nor there in this narrative…I digress.)

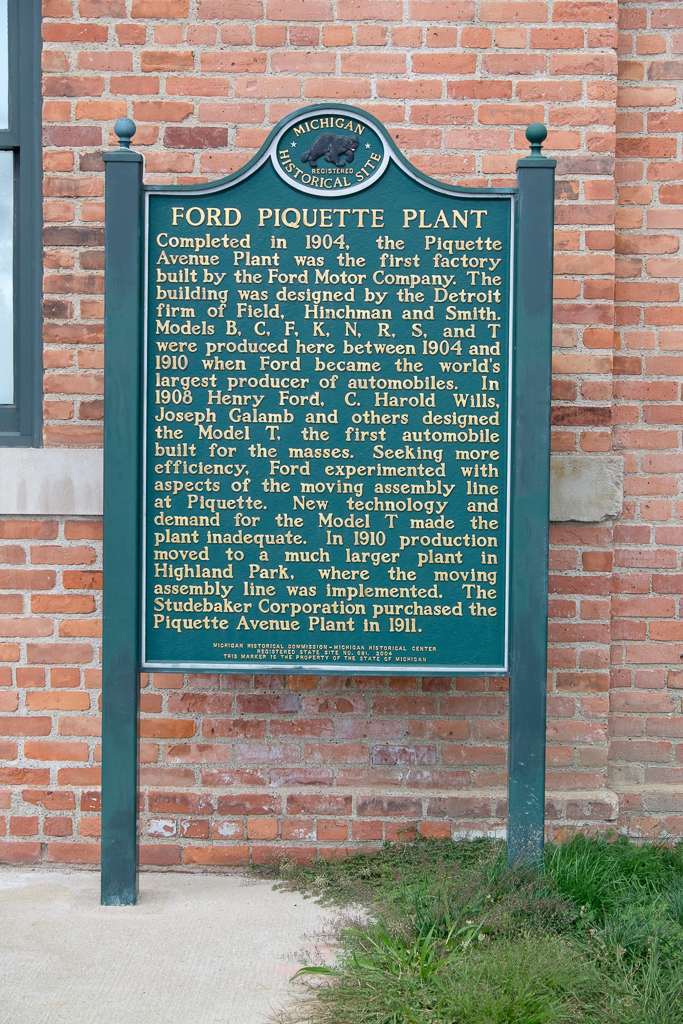

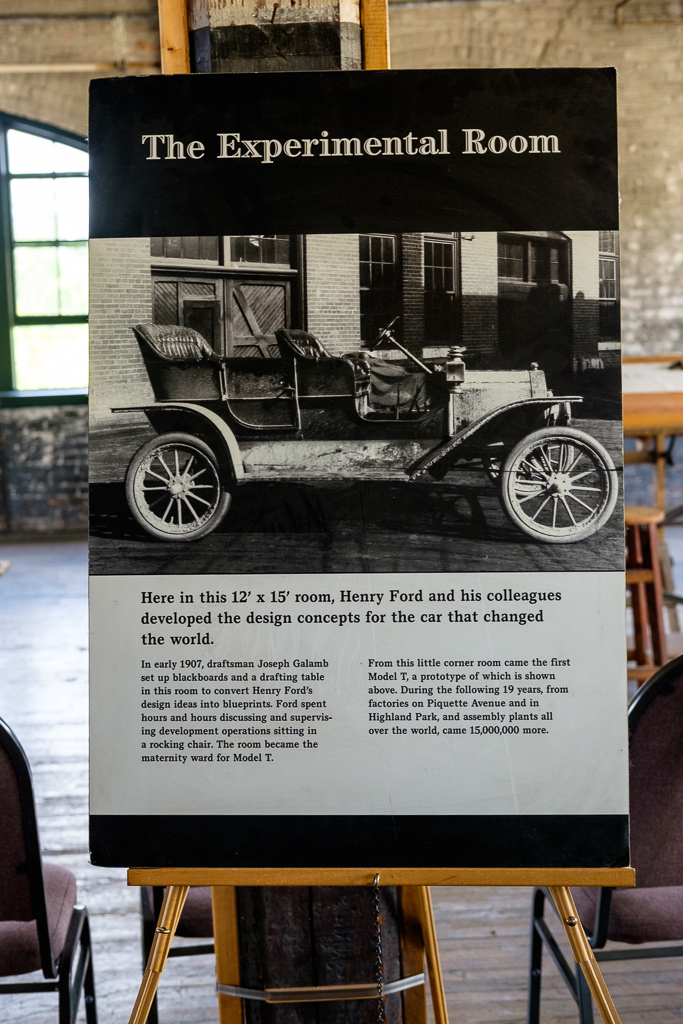

Let’s start at the former Ford Piquette Avenue plant – a hugely historic building. This was the birthplace of the Model T. There’s a great collection of old Fords there, including that very sweet 60s Mustang in the pix below. The early experiments using a moving assembly line to make cars were also conducted there. It’s a fine visit. I spent several hours there.

The next building is the Highland Park plant designed by the architect Albert Kahn and also tremendously historic. Ford moved there in 1910 and sold the Piquette Avenue building to Studebaker. Highland Park was the second US production facility for the Model T and the first factory in history to assemble cars on a moving assembly line. Its importance cannot be understated as a matter of US (and world) industrial heritage. It’s closed to the public now, and as I understand it, the building has been unoccupied and decaying for years. It was also known as the Crystal Palace – look at all those windows in the Highland Park photos below. There seems to be an effort underway to save the building. It’s a dodgy neighborhood. My friends took me there on a driving tour of the city we did together on one of the days I was in the D (thank you again, Todd and Terri). I got out of the car to get a few quick pix, and then we drove on. I have to say, it didn’t feel particularly safe around there. Check out these amazing historic pictures of the plant I found online.

As an aside, Kahn did a number of buildings for Ford. SF Bay Area friends and family, Kahn designed the former Ford plant in Richmond, CA (which was the largest assembly plan ever built on the West Coast – closed 1955). Another building with walls consisting of large, multi-pane glass windows. As you can see below, it is now part of the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historic Park.

By the time you get through this post, you will be thinking I should have called it “Albert Kahn’s Detroit”. It seemed like his buildings were everywhere. Read more about Kahn here.

Next we head (back) to the Milwaukee Junction Area of Detroit which is somewhat of an industrial wasteland. The Ford Piquette Avenue building is in this area. Many overgrown vacant lots, fenced off abandoned factories, burned out and abandoned houses, here and there a church. It’s a pretty foreboding area. It once was the cradle of Detroit’s heavy manufacturing, and is described as having been one of the most important concentrations of industry in the world.

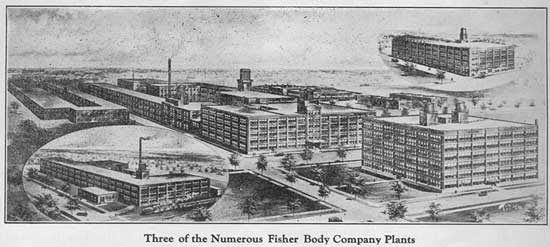

A number of the shots in Milwaukee Junction are of the iconic Fisher Body Plant No. 21 ruin (Kahn, 1919), at 700 Piquette Avenue (this is very close to the Piquette Avenue plant). There are some industrial buildings still in use around there; it’s not all industrial wasteland. The restored New Center Stamping company building at 950 E Milwaukee St. (constructed in 1922 and originally known as Fisher Body #23) in this set was the filming location of the plant where Rabbit (Eminem) worked in the film “8 Mile”.

Next we will (briefly) look at two architectural beauties in the New Center area – two examples of what was being built in Detroit during the height of its importance. Cadillac Place, formerly the General Motors Building, is at 3044 West Grand Boulevard and now houses a number of State of Michigan offices. Completed in 1922 and a Kahn, it was the General Motors world headquarters from 1923 until 2001. Nearby is the landmark Fisher Building at 3011 West Grand Boulevard, 1928 (another Kahn), and truly an art deco masterpiece. We’ll return to these buildings in a future post.

After New Center a brief stop at the Ford River Rouge Complex automobile factory complex located in Dearborn. Here’s what the National Park Service site has to say about “the Rouge”:

“By 1927, when Ford shifted its final assembly line from Highland Park to the Rouge, the complex included virtually every element needed to produce a car: blast furnaces, an open hearth mill, a steel rolling mill, a glass plant, a huge power plant and, of course, an assembly line. Ninety miles of railroad track and miles more of conveyor belts connected these facilities, and the result was mass production of unparalleled sophistication and self-sufficiency.”

By the mid-1920s, the Rouge complex was said to be “the greatest industrial domain in the world”. There are also Kahn buildings at this site. That 60s style Ford building there caught my eye. I am going to go out on a limb and say it’s not a Kahn! There are tours of the complex; perhaps another visit.

Lastly, we’ll return to Detroit from Dearborn to the Renaissance Center complex on the Detroit River opposite Windsor, Canada. It was conceived by Henry Ford II in the early 1970s and financed primarily by the Ford Motor Company. It is now owned by General Motors; among other things, it’s used by GM as its world headquarters. The first phase opened in 1977, and two additional office towers (Tower 500 and Tower 600) opened in 1981. Meh. It’s certainly flashy, I’ll give it that.

John Portman was the principal architect of the Renaissance Center; I recently read that he passed away. His firm did Atlanta’s Peachtree Center; it also did other well known buildings such as the Embarcadero Center in San Francisco, the Bonaventure in Los Angeles, and the Hyatt Regency Atlanta. Many of these projects have been described as “inwardly-oriented spaces” and “insular environments” turning their back on the city street. That’s an apt description of RenCen in Detroit – a “city within a city” isolated from the nearby downtown. It doesn’t do much for me anno 2018; it doesn’t relate at all to the nearby historic downtown. I do recognize, however, that there were very different approaches to and understandings of urban redevelopment in the 1970s. In the SF Bay Area, many of us liked Portman’s Hyatt Regency San Francisco back in the day.

I guess one has to consider the time period in which the RenCen was conceived and built. Only ten years before its opening, the Detroit riots occurred and the city burned. In the 60s and 70s crime there was high, and the city seemed to be dying. People certainly were. The gleaming fortress RenCen seemed to be the 70s answer to the urban decay and decline. It was meant to be a catalyst for the city’s renewal. At the time it was the world’s largest private development. Some say now that it stands as a symbol of how not to revive a downtown area. For a detailed history of the project, go here.

That’s all for now. There’s much more Detroit to come. The next post will have more Detroit industrial heritage but from an artistic perspective – Diego Rivera’s “Detroit Industry Murals” at the superb Detroit Institute of Arts.